CHAPTER 9

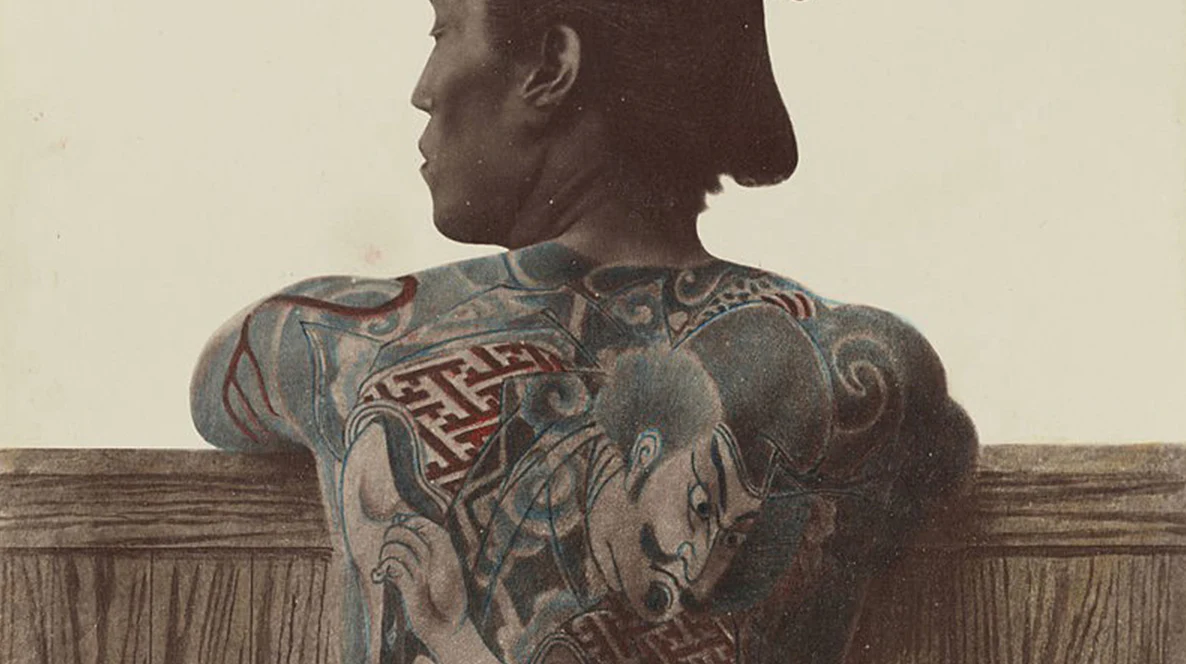

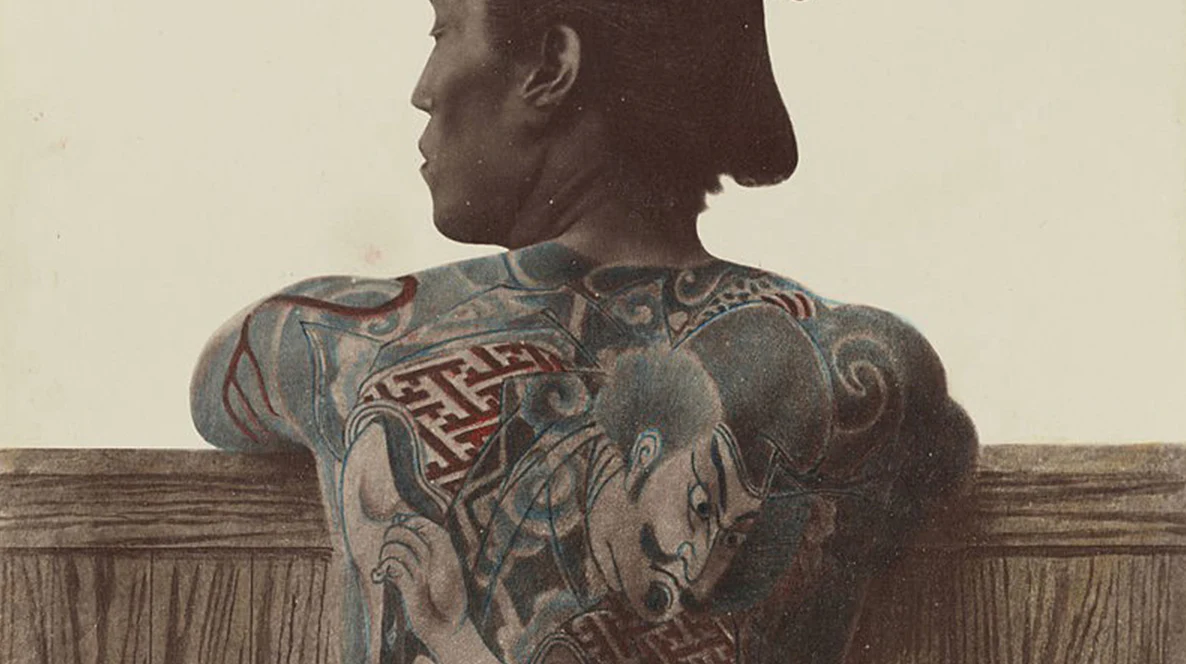

Irezumi - which translates as “insert ink” - became so popular during the Edo Period that the samurai made them illegal.

Although tattooing in Japan goes back 5,000 years (we know this from tattooed Dogū figurines from the Jōmon period), the signature style of Japanese body art, Irezumi, actually only goes back a few centuries. So what happened in between? The Ainu people continued to practice their body art traditions right up until the 19th Century. At this point, Japan was opening up to the world for the first time — after hundreds of years of isolation — and wanted to present a modern, unified image. The Ainu people’s ‘barbaric’ tattoos didn’t fit with this image, so they were “prohibited as a way to appear civilised and sophisticated” according to BodyLore.

Publish Date in article

Japan’s negative view of body art seems to have been influenced by the Chinese who “had a long-standing aversion” based on Confucian philosophy.

In 1614, shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu quoted Confucius doctrines when he said, “body, hair and skin we have received from our father and mother; not to injure them is the beginning of filial piety. To preserve one’s body is to reserve god.” When Japan was a strict, military dictatorship you’d think tattooing would have disappeared completely. But it didn’t. Instead, Japanese tattooing happened on the fringes - practiced by sailors, artists and the working classes. And then, just like in Europe, the popularity spread to criminals.

The ‘criminalisation’ of tattoos has been viewed as a form of classism: a way of preventing artistic expression amongst the lower classes. But it also proved a catalyst – many Japanese people rebelliously got inked anyway. In fact, the Edo Period is described as “the golden age of tattooing.” “Artists rebelled against the strict social hierarchy of the military dictatorship of the Tokugawa shogunate through art, making Irezumi an aesthetic choice... Tattoos became so popular that the samurai made them illegal. But due to difficulties enforcing this law, Irezumi continued to be created,” according to Japanese Visual Culture.

Publish Date in article

But it wasn’t all about rebellion.

The meaning of the tattoos was the appeal. Sometimes for protection - and sometimes for love. Courtesans during this era were said to have “pledged their eternal love by incising the lover’s name in their skin,” according to Nippon. “In 1872, the Japanese rulers issued a national ban on tattoos. After this, it was mainly the Japanese mafia known as the Yakuza that kept the practice of tattooing alive. Because of this trend, many Japanese citizens assumed people with tattoos were members of Yakuza, so tattoo owners often faced prejudice and fear from the community,” according to Japanese Visual Culture. As the Japanese public’s fear of the Yakuza grew, so did their fear of tattoos in general. “As one of (the Yakuza’s) greatest trademarks, tattoos are a sign of strength, as a traditional Japanese tattoo takes quite a while to complete. Tattoos symbolised strength, courage, toughness, masculinity, and a sense of solidarity with fellow gang members,” writes Mieko Yamada in Japanese Tattooing from the Past to the Present. And yet the associations weren’t all negative. Tattooed heroes called ‘kyōkaku’ (translated as chivalrous commoners or street knights) featured prominently in the popular culture of the Edo period. They were seen as “outlaw heroes who protected the weak and innocent from the powerful and corrupt,” according to Nippon.

Publish Date in article

“The Yakuza sought tattoos because they were a painful way to prove one had courage and because of their permanent nature. Since tattoos were illegal, getting one made them outlaws forever.” according to BodyLore.

In the West, fascination with Japanese tattooing was also growing. “Ironically, while Japanese authorities sought to squelch the work of tattoo artists in the hopes of presenting a squeaky clean image to foreign powers, Western sailors began to visit the studios of various masters in Yokohama in search of ink. Even some Western dignitaries, including the Duke of York, who later became King George V; and the Tsarevich of Russia, who later became Tsar Nicholas II, went under the needle,” according to The Diplomat. And then came World War II, which suddenly intensified the demand for tattoos – for completely different reasons. In Japan, there was “a rush among young Japanese men to get Irezumi in attempts to evade military conscription; the Imperial authorities perceived people with tattoos as nonconformists and potential sources of trouble within the armed forces,” according to The Japan Times.

Publish Date in article

Then at the end of the war, following the Japanese surrender, thousands of US and commonwealth soldiers were deployed to Japan. Comparing the elaborately complex Japanese Irezumi body art with their European style tattoos, they realised they were “scratching the surface of of what could be achieved with needle and ink,” the article continues. Demand for Japanese Irezumi surged and Japan responded by lifting the ban – but only for foreigners. “As soon as (soldiers) set eyes on the Irezumi worn by Japanese delivery men and rickshaw pullers, many wanted one as a souvenir of their stay. To cater to their demands — and in contravention of its own ban — the Meiji government begrudgingly permitted Japanese tattooists to set up shop in the areas set aside for foreigners, such as Yokohama, Kobe and Nagasaki. Working behind doors closed to Japanese people, these tattooists inked, by some accounts, three-quarters of all visitors to Japan.”